Who Are We? A Lesson from the Life of James Cone and his Love for the Church

By Rev. Nikia Smith Robert, Contributing Writer

In rural Arkansas, at Macedonia AME Church, a young boy sat in the pews with his mother. He listened to a Gospel that proclaimed liberation for the oppressed and heard the sultry sounds of spirituals signifying the suffering of Black people. He contemplated the theological dissonance between white Christianity and racial inequalities in Jim Crow South. Convinced by the connections between the cross and the lynching tree, the late Rev. Dr. James Hal Cone synthesized the faith of his mother with the prophetic fervor of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the political agitation of Malcolm X. He concluded that Jesus is Black and God is on the side of the oppressed.

As a son of African Methodism, Cone became the “Father of (Black) Liberation Theology.” He is reputed to be the greatest American theologian of the twentieth century. Cone made an indelible contribution to the project of liberation, which is deeply informed by a tradition of resistance that is the epitome of the Gospel and at the center of our Zion’s history. In considering how to extend Cone’s legacy, we must contemplate the ways in which Black liberation theology is relevant for the future of the AME Church.

In a viral video taken at a 2013 Vanderbilt Divinity School conference, Cone passionately discussed his book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, in connection with the mission of the Church. During the fielding of questions, someone asked him, “Considering the paradox of the cross where the hope of our ancestors came by way of defeat, what is missing today? How does the Black Church, serving in this present age, resurrect that paradox?” Cone responded, “It is that question that made me write the book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree. I think the Black Church has forgotten about where it came from.” Cone made a prophetic indictment and qualified it with a targeted reference to the AME Church. He chided, “They don’t know who they are.” In the same forum, however, Cone unashamedly declared that the AME Church was formidable in his faith and foundational for his intellectual development. Thus, in the wake of his death, and in reverence of his life, it behooves us to examine ourselves. In the tensions between critique and celebration of our Church, we must rightfully ask, “Who are we?”

Born out of racial inequalities in 1816, our founding father Richard Allen became the first elected and consecrated bishop of the AME Church. Bishop Allen authorized the Rev. Jarena Lee to preach at a time when women were considered unworthy of a call to the Gospel.

Black nationalist and state legislator, Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, expanded our Church to the continent of Africa. Bishop Daniel Payne was one of the founders of Wilberforce University and emphasized the pivotal role of education in racial uplift. Bishop William Paul Quinn worked with the underground railroad and antislavery movements. In the tradition of social justice that marks the genesis of our Church, Bishop Vashti McKenzie became the first female elected and consecrated as bishop in our denominational history. AME member, Rosa Parks architected the Montgomery Bus Boycott that became an impetus for the Civil Rights Movement. Our Church inspired the scholarship of Womanist Theology and Black Liberation Theology through the pioneers of Drs. Jacqueline Grant and James Cone, respectively. We are the oldest black denomination in the United States with a remarkable history but how relevant are we for today’s struggle for justice? How do we bridge our prophetic historical witness with a purposeful present-day protest?

In the spirit of Cone, we must challenge our complacency, devise a connectional campaign of resistance, and organize locally to radically advocate for those who are oppressed, nationally and globally. Black bodies are unjustly dying. Their blood, not just Jesus’ blood that we sing about every First Sunday, is calling us. We owe it to our people and to our Zion to reformulate an ecclesial identity that infuses the priestly with the prophetic to proactively dismantle the idolatrous spirit of empire, both in our church and beyond our doors. We must ask, amid mass incarceration and militarization, “Who are we?” We must ask amid poverty and patriarchy, “Who are we?” We must ask amid heterosexism and homophobia, “Who are we?” We must ask amid isolationism and institutionalism, “Who are we?” We must ask amid apathy and anti-black racism, “Who are we?” We must become the Church who assumes the risks associated with the faith of our foremothers and forefathers to advance the project of liberation for our contemporary context.

Cone states in The Cross and the Lynching Tree, “Humanity’s salvation is available only through our solidarity with the crucified people in our midst.” To know who we are is to know who we are in relation to the oppressed. Our relevancy as a Church may very well be measured not by our praise but by our purpose and not by our liturgy, but by serving the least of these.

Black Liberation Theology is relevant for our future because it teaches us that to be Christian is to radically engage the struggles of Black people and all who suffer injustice. The inimitable and incomparable Rev. Dr. James Hal Cone, a son of Methodism, has transitioned from the pews he once shared with his mother at Macedonia to a seat in Heaven. In his honor, may we stand with the God of the Oppressed and in solidarity with the crucified people in our midst. May we never lose sight of who we are as the sons and daughters of Sarah and Richard Allen, Jarena and Rosa, Payne and Turner, Quinn and the Emmanuel Nine, Jesus Christ and James Cone. This great cloud of witnesses provides a critical clarion call to (re)cast our ecclesial identity in concert with the moral imperatives and Christian mandates to do justice. May we challenge our complacency with a conviction to serve as change-agents, celebrants, and contributors in the fight for freedom because of who we are. We are AME.

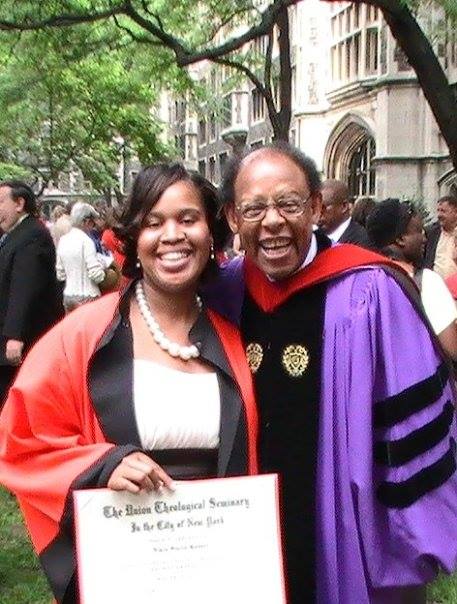

Rev. Nikia Smith Robert, affectionately known as “Reverend Daughter,” enthusiastically embraces her divine purpose to preach, teach and engage in social activism. She is an ordained itinerant elder serving on the ministerial staff at First African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Pasadena, California. She is currently pursuing a Doctor of Philosophy degree at Claremont School of Theology where her scholarly interests focus on the religious and political intersections of race, gender and class as it pertains to Black women and mass incarceration. Rev. Robert can be found on Facebook at Reverend Daughter Ministries, Twitter @reverendaughter, and her personal website at www.reverenddaughter.com. Rev. Robert was a student of Dr. James Cone at Union Theological Seminary (class of 2009).