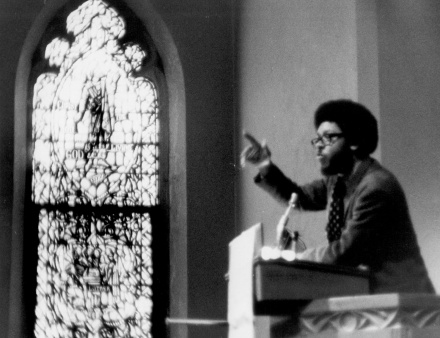

Liberating Lessons from the late Dr. James Hal Cone

By Rev. Teresa Fry Brown, Ph.D., Executive Director of Research and Scholarship, AME Church

The death of the Rev. James Hal Cone, Ph.D. on April 28, 2018, refocused the attention of many in the church and the academy on the life of one to the most important and prolific theologians of the 20thCentury. Dr. Cone was the prophetic founder of Black liberation theology and some would argue the architect of liberation theology. In his widely acclaimed book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, he began to write fully engaged in composing liberation theology in 1968, two months after Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination and while worshipping at Union AME Church in Little Rock, then pastored by his brother, the late Dr. Cecil Cone. He said, “I wanted to speak on behalf of the voiceless black masses in the name of Jesus, whose gospel I believed had been greatly distorted by the preaching theology of white churches.” In Black Theology and Black Power, he described his creative process. He said, “[S]omething happened that I can’t explain. It seemed as if a transcendent voice [was] speaking to me through the scriptures and the medium of African American history and culture, reminding me that God’s liberation of the poor is the primary theme of Jesus’ gospel.”

These selected quotes seem to be a combination of Bishop Richard Allen’s missional interpretation of Luke 4:18-19; Bishop Henry McNeil Turner’s proclamation that “God is a Negro;” Cone’s experience with white supremacy in church, society, and academic apartheid; the creativity of the Black Arts Movement; and the protest embers of the Black Power Movement. Further inspired by the Detroit Riots of 1968 that resulted in the deaths of 43 people, he said, “I heard the voices of black blood crying out to God and to humanity.”

These liberating words were not produced by a demigod, ensconced in an ivory-towered classroom or an angry Black man with a hatred for the church or people of faith. These transformative words were composed by one born in Fordyce, Arkansas and raised in Bearden, Arkansas, as the sonof social activists Charles and Lucy Cone. Charlie Cone, his father, filed a lawsuit against the Bearden School Board to desegregate the schools during the early 1950s. He was nurtured in the womb of Macedonia AME Church in Bearden, Arkansas, and ordained in the AME Church.

Dr. Cone was a scholar par excellence who began his undergraduate studies at Shorter College and obtained a B.A., Philander Smith College, 1958; a B.D., Garrett Theological Seminary, 1961; an M.A., Northwestern University, 1963;and a Ph.D., Northwestern University, 1965. He taught theology and religion at Philander Smith College and Adrian College (Michigan) prior to moving to Union Theological Seminary in New York in 1970. He taught at Union Theological Seminary in New York for 50 years. He was awarded the distinguished Charles A. Briggs Chair in systematic theology in 1977and assumed the Bill & Judith Moyers Distinguished Professor of Systematic Theology Chair in 2017.

Driven by the realities of Jim Crow, a childhood in a lynching culture, adult-charged racism, the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin King, a love of the spirituals and the blues, and the activist writings James Baldwin, Dr. Cone began to formulate a different way of engaging God-talk in a prolific body of theological texts. These include Black Theology & Black Power(1969), A Black Theology of Liberation(1970), God of the Oppressed(1975), Black Theology: A Documentary History(with Gayraud Wilmore 1979), My Soul Looks(1982),For My People: Black Theology and the Black Church ( 1984), Speaking the Truth: Ecumenism, Liberation and Black Theology (1986), Martin and Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare(1991), The Spirituals and the Blues (1992), Risks of Faith: The Emergence of a Black Theology of Liberation 1968-98 (1999),The Theology of Martin Luther King, Jr. (2013),The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011), and the forthcoming memoir , Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody: The Making of a Black Theologian (November 2018).

He was honored with the 2018 Grawemeyer Award in Religion, jointly awarded by Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary and the University of Louisville for The Cross and the Lynching Treeshortly before his death. He is quoted as saying he wrote the book as a conversation starter to explore the deep wounds of lynching, white supremacy and every kind of injustice. He said, “The crucifixion was clearly a first-century lynching. Both are symbols of the death of the innocent, mob hysteria, humiliation, and terror. They both also reveal a thirst for life that refuses to let the worst determine our final meaning and demonstrate that God can transform ugliness into beauty, into God’s liberating presence.”

Despite all his renown, Dr. Cone had a way of being self-deprecating and then forcefully standing on his beliefs. His distinctive voice could be calm and affirming one minute and passionately piercing as he described his beliefs the next. He was not afraid of a fight based on principle. He gave searing critiques of both white theologians and the Black Church. Yet, he constantly reiterated his love for the church and what he owed as the AME Church. I often say to my students, “The prophet must love the people enough to want them to live.”

I believe Dr. Cone never turned his back on the church. He knew when to step away and when to re-engage. In my few conversations with him, he was working to help the church return to its prophetic center.

Dr. Cone was a member of the Adams Coleman Williams Distinguished AME Scholars Guild. Some of the liberating lessons this professor preacher and shared by precept and example include always remember where you came from and what you learned there. Bearden, Arkansas, and the AME Church are referenced in many of his works.

Second, one must be ready to risk ostracism and critique when God gives new ideas or approaches to age-old practices or beliefs. If God directed you, things will come to pass.

Third, when your work is attacked, critiqued, or deconstructed, it should push you to think even deeper. Accept that you said something worthy of someone caring enough to read it.

Fourth, know when to apologize. Dr. Cone rethought his positions on issues of gender and class equality and acknowledged his omissions in constructing Black liberation theology.

Fifth, practice does make perfect. Dr. Cone repeatedly shared that he would write, study, and read eight hours per day to remain focused on his work, continue to learn, and be productive.

Sixth, a tree is known by the fruit it bears. There are Black scholars across the world who were Dr. Cone’s students, were taught by someone who was one of his students, read one of his texts, and were either positively or negatively impacted or in some way have been beneficiaries of his groundbreaking body of work.

Seventh, you can’t judge a book by its cover. Following a lecture in The Cross and the Lynching Treeat Vanderbilt’s “The Black Church’s 11thHour” Conference, Kelly Miller Smith Institute on Black Church Studies on April 3, 2013, Dr. Cone witnessed, “Without the AME Church and Shorter College, I do not know where I would be.” He credited the Lord with all he did and became citing, “I was not the brightest. I was not the smartest. I just said I’m going to keep doing the best I can do every day.”

Dr. Cone was a prophetic voice, often crying in the wilderness. In a 2008 NPR interview, he summed up his work, “The core of black liberation theology is an effort—in a white-dominated society, in which black has been defined as evil—to make the gospel relevant to the life and struggles of American blacks, and to help black people learn to love themselves… It’s an attempt to teach people how to be both unapologetically black and Christian at the same time.” Given the current social-political climate, perhaps it is time for the church, scholars, and people who desire justice to read, revisit, discuss, and put into practice the substance of Dr. Cone’s prophetic witness.

The Rev. Teresa L. Fry Brown, Ph.D. is the Bandy Professor of Preaching at Candler School of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. She is the first tenured Black female Professor at Candler and the third Black female to attain the rank of Full Professor at Emory. Dr. Fry Brown was elected in 2012 as the first woman and the fourteenth Historiographer of the African Methodist Episcopal. As Historiographer she is editor of the A.ME. Review and serves as the Executive Director of Research and Scholarship. With numerous scholarly works published, Dr. Fry Brown is a member of the American Academy of Religion, Society for the Study of Black Religion, and the Academy of Homiletics. She is an ordained Itinerant Elder in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and an Associate Minister at New Bethel A.M.E. Church, Lithonia, Georgia.